August 13 falls on a Saturday this year. I remember once, over half a lifetime ago, when it was Friday the 13th. It was 34 years ago… and I was 32. And I was coordinating the marketing set-up for all these 33 RPM albums. Those are the good numbers.

It was August of 1982, and Epic Records was treading water a bit. The good news was that the Rocky 3 soundtrack had just been certified multi-platinum, driven by the indelible “Eye of the Tiger” single by Survivor. “Good Trouble,” REO Speedwagon’s follow up album to the many-times platinum “Hi Infidelity” was flagging, with only one Top 10 single, “Keep The Fire Burnin’.” The only other big hit I recall was Bertie Higgins’ “Key Largo,” a big radio record that just didn’t translate to album sales.

I was three years into being a product manager at Epic. I had a few successful projects under my belt with The Charlie Daniels Band, The Clash, The Isley Brothers, Luther Vandross, and Steve Forbert. I had managed to achieve one of those titles straight out of the Rolling Stones’ song “The Under Assistant West Coast Promo Man.” Mine was Associate Director, East Coast Product Management.

But the work had been hard, as I had inherited two intense and laborious projects that impacted Epic’s bottom line severely. One was Meatloaf, whose follow up album to the astounding success to “Bat Out of Hell” had finally arrived in the fall of 1981. It had been a torturous road of a lost voice and lost opportunity. Meat was unable to record the original follow-up album, “Bad for Good,” due to severe vocal issues that loomed as a likely career-ending tragedy. That album became Jim Steinman’s debut that simply could not live up to 40 million plus sales of “Bat Out of Hell.”

However, by the time we staggered out of the box with Meat’s return with “Dead Ringer,” the momentum was all but gone. And despite the passion the Cleveland International’s Steve Popovich, Stan Snyder, and Sam Lederman brought to the release, the U.S. sales results were gut-wrenching. We spent a ton trying to make it happen, and the CBS Records finance people were quick to remind us what geniuses we were.

In the meantime, the company was working desperately to get Tom Scholz and Boston to deliver their third album. It had been four years since “Don’t Look Back,” the huge follow-up album to their astonishing self-titled debut. In those days, such a gap in the timely release of succeeding albums was almost unheard of. However, Tom Scholz, the group’s creative nucleus, had established a reputation as the ultimate perfectionist. Epic senior management agonized over the delays in delivery. And the bean-counters at CBS Records were demanding to know how we were going to replace those expected sales numbers.

Our A&R people, in desperation, had pulled together some of the members of the group, who were also frustrated with Scholz’ possession of the creative process, and in 1980 released a solo album by Boston guitarist, Barry Goudreau. This ultimately infuriated Tom, and I became one of the last links attempting to mend the fences and fuel his desire to deliver that third album to Epic. By August of 1982, that still had not happened, and ultimately it never did. In fact, the situation devolved into a massive lawsuit that extended into the next nine years. However, that’s another blog story for the future!

So on Thursday, August 12, 1982, I got a call from my boss’s boss to come to his office. It was not an unusual occurrence in the socially relaxed environment of a record company at that time. The heads of the company would check in on conversations that a product manager might be having with an artist or their manager. It’s a people business.

However, on this day the door closed behind me, and I was quickly informed that on the next day, Friday the 13th, I was to sit down individually with about half of the east coast marketing staff to inform them that they had been laid off. I was sworn to secrecy until the process would begin the following morning. As the Associate Director, I had not really had any power to hire and essentially had only a little authority. As a senior product manager, I helped guide my new counterparts about the job and how to get it done and I also was involved in assigning what product manager would handle new artist signings. That usually came with some strong recommendations from senior management as well as from the people in A&R, who had their favorite product managers. Suddenly, life became all too real. In a moment, I had been drawn into informing people that their lives were changing. I was told I would be given envelopes the following morning that would indicate who I was to let go and I was given instructions on how to handle each meeting.

In those days, working for a big major label like Columbia, Epic, Warner Brothers, Atlantic, MCA, or Polygram, meant that you had a gig for the foreseeable future. I knew many, many people who had worked at the company for ten, twenty, and thirty years. It was a paternal environment. We were mentored to be there for a career. And although it was still a daunting environment for women executives, our department was beginning to open up to those opportunities. In 1982, after the explosion of album sales in the ‘70s, a mass lay-off was unheard of and virtually unfathomable.

Black Friday arrived with dread. As I remember, I was given roughly five envelopes that morning. By the time I finished the first meeting and opened the door to leave that product manager’s office, I was already numb. The hallways were already in chaos. People were darting in and out of offices, spreading the news of who the first victims were and speculation was wild about what was to come and how far this bloodbath would go. Like a robot, I went on to repeat the process with department mates and colleagues… and above all, friends.

Somewhere along the line, I discovered that my boss had been let go, and no provision had been made to inform his secretary. She was in tears, asking me for help and what was going on. She had been missed in the process, and when I inquired with H/R, one more meeting was added to my day.

Times have changed, and being laid off today is a common experience, and one that most people understand they should not take as an indictment upon their performance or their integrity as an employee. However, since lay-offs had been non-existent at that time, the people being laid off took it very, very hard. All told, over 300 people left us that day. These were all talented, hard-working people. CBS Records closed nearly half of our 21 branch offices across the U.S. It was Black Friday, indeed.

In the wake of that August 13, 1982 shock, the dust slowly settled. A semi-cold record label had paid the price for not delivering the massive sales to drive the corporate ship. A certain remorse set in. The closed doors of empty offices and the half-filled secretarial bays were daily reminders that these records had to sell. Had we completely lost our mojo? Did we really know how to do this? Survivor’s guilt settled in hard. We had been jolted into the realization that these were jobs we had to do and there were consequences if we weren’t successful.

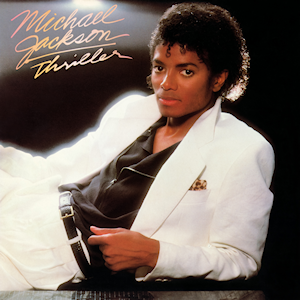

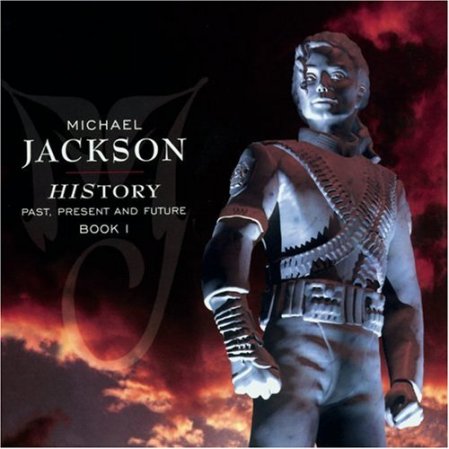

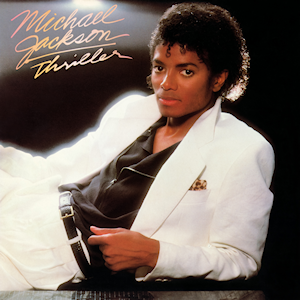

And just at that point when we were trying to figure out if this whole concept of the crazy music business still worked, something happened to us. Out of the ashes it came, like something no one had ever seen before. Thriller!

Oh, I’m not going into the whole story of the most powerful album release in the history of the music business. If you want that story, just listen to the album… it speaks volumes!

What remains remarkable to me is how that album and its success transformed a record company and the people who worked for it. It was only weeks after that terrible August day that we listened to Michael Jackson’s album in the 13th floor conference room. Oh, we knew that the duet with Paul McCartney, “The Girl Is Mine,” was a hit! How smart did we have to be?

Here we were, once again, trying to follow a multi-platinum album with huge expectations – from our finance department – as well as radio, retail, and the public! Meatloaf, Boston, even REO, lurked in our recent past. The daunting challenge of matching Michael’s five million unit U. S. sales success with “Off The Wall” was hard to grasp. We were simply relieved to have that first single to momentarily relieve the pressure.

Within 3 ½ months of Black Friday, we had an album hit the streets that changed our lives forever and the direction of Epic Records for at least a decade to come.

But “Thriller” arguably changed other artists’ lives in its wake. Epic Records got hot. Epic got its swagger back. “Thriller” opened up doors as it sold and dominated airplay and video play for its many singles. It created leverage for our promotion people and our sales and distribution people. Subsequently, we broke Culture Club and Cyndi Lauper and Sade; each winning the Grammy for “Best New Artist in 1984, ’85, and ’86. And they all sold multi-millions.

In those next 36 months, we broke Quiet Riot (“Come On Feel The Noize”), Til Tuesday, (“Voices Carry”), Gloria Estefan & The Miami Sound machine (“Dr. Beat”), and re-broke REO Speedwagon (“Can’t Fight This Feeling”). We even broke Springsteen knock-off John Cafferty & The Beaver Brown Band, for God’s sake! You remember “On The Dark Side” from the “Eddie and the Cruisers” soundtrack? We sold millions and millions of albums!

Of course, all of these artists and their songs succeeded on their own merit. However, it was the momentum of the Epic Records promotion, publicity, and marketing team, and the muscle of the CBS Records sales and distribution machine that opened the door and maximized these successes.

Among those successes, I believe a few of them would have never gotten the full shot if not for the success of “Thriller.” We got our mojo back. We used the leverage of one success to help us break others. It was a magical time that I know many of my colleagues will remember as the revenge of Black Friday. It is simply another way that great music transcends and changes the world.

Yesterday, almost 34 years removed since Black Friday, it was announced that Epic Records was moving their HQ to LA. I’m sure it will change many lives and some will chose not to make the move. I’m sure, whatever that move is meant to fix, would be better served if another “Thriller” dropped from the sky. In 1982,… We were lucky!

I know there are more examples of hits and hit artists opening the path other artists. I’d love to hear those stories!

*****

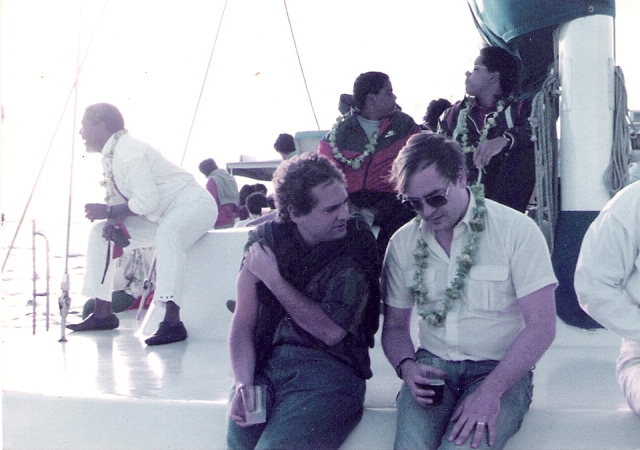

Harvey Leeds and I discussing the music business in Hawaii.

Addendum:

One of the joys of writing an occasional blog story is that I hear from so many former colleagues and friends who have shared so many amazing experiences in the old school music industry. Along with the warm notes expressing mutual appreciation for those times and those experiences, I always get some great feedback from those friends and colleagues who often remember specifics for better than I do. They send me notes to correct or expand or give me an entirely different side of what they saw happening. I haven’t written a blog story yet where I got it all right.

One of the reasons I write so infrequently is that there is so much texture and detail to most of these stories that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to capture it in a few blog pages. I have written several pieces that I’ve never posted because they have devolved into a blur of conflicting details that blew up my origin al premise. Writing sometimes just makes me discover that I just don’t have the full story.

I received a note from Harvey Leeds regarding my “Black Friday” blog. He posted on Facebook, “Ahem—rewriting history like every great journalist!! Thanks for the memories—some of them.”

I write this addendum, because I take Harvey’s comments very seriously. He was a central player in the history of Epic Records. Our time together at Epic overlapped for roughly 20 years, and his time there extended beyond mine. We worked together on countless projects, argued how to do it, occasionally blaming each other when an act hit the wall, and we celebrated many successes together.

My intentions for the “Black Friday” blog was to remember a day that is indelible in many of our minds and to connect it to the corporate moves that continue to this day, upon Epic’s announcement that they are moving HQ to the West Coast. It was also to illustrate how multi-platinum success, evolving out of the mid-‘70s, was becoming a requirement at major labels. On some level the powers-that-be did not want to hear how we were developing acts. They just wanted big numbers.

In that blip of a moment when Epic didn’t have that huge multi-platinum release, we paid for it, as did Columbia Records and the CBS Records Distribution staff. In my artist examples, I certainly short-handed my examples. Between Epic/Portrait/CBS Associated Labels, we easily had 70-80 artists on the roster. My rock artist references essentially included those that crossed over to multi-platinum pop success. We had many other successes at rock and R&B that apparently didn’t move the numbers people at CBS at the time. There were platinum successes with Aldo Nova and gold with Eddy Grant, who also won the Grammy for “Best R&B Song” with “Electric Avenue.” I know I am missing others.

My ultimate point was that the arrival of “Thriller” changed much for Epic Records. Our promotion people, led by Frank Dileo, Larry Douglas, T.C. Tompkins, Paris Eley, Harvey Leeds, and Bill Bennett, leveraged that Michael Jackson success powerfully and artfully to enhance the opportunities and careers of other artists on our roster.

I appreciate Harvey’s note, because it reflects his pride and his view on our collective history. In my humble opinion, I thought Harvey was one of the best at using that ‘success leverage’ to benefit of our artists and all of us who worked at the label.

I have no notion that my blog could have any material effect on “re-writing history.” To me, one of the great opportunities in putting the effort into creating this blog is to get the rich feedback, perspective, reflections, and stories of the friends and colleagues who shared this amazing music life that we had. Nothing would be better than for it to be interactive with the depth that can only come from our collective memories.

Last year, Harvey, Chris Poppe, John Doelp, and I had an uproarious lunch, mostly inspired by Harvey’s take on the people and events that dotted our past. I should have taped it! I’m sure you would all have appreciated the expletives and even some of the libel that made our two-hour plus lunch a hilarious episode. As Chris said as we were leaving the restaurant, “That was like a vacation!”

So while I agonize putting my foot in my mouth again and writing down sometimes rusty memories, I hope you’ll all give me a little poetic license… because some of it is actually true!

Save

Save